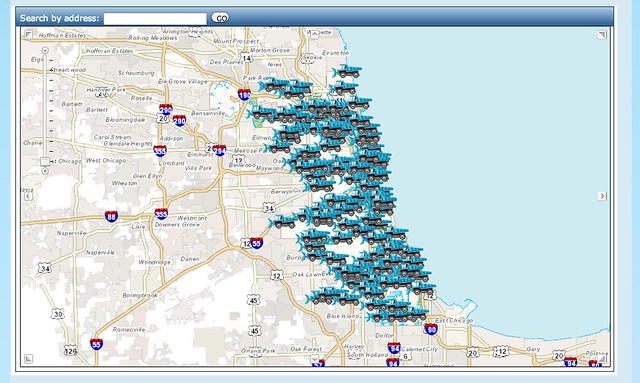

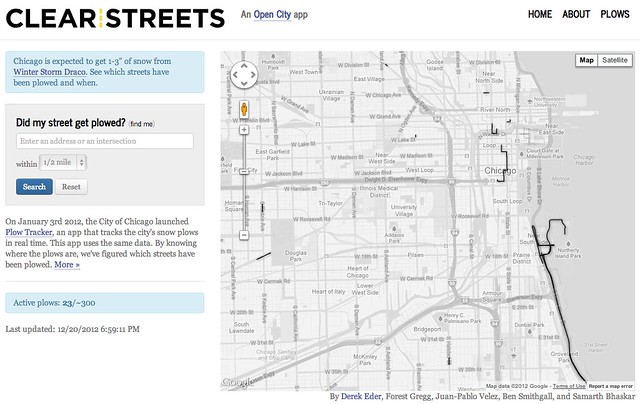

The civic hacking community in Chicago has produced a variety of civic web applications based on open data provided by local government here in Chicago. These apps do things like show economic indicators in fun ways, let you know if your car was towed, and how & where to get a flu shot.

There are lots of reasons why civic hacking works here in Chicago— a rich baseline of data and technology, an engaged developer community, real discussions with government about policy and data, and the support of institutions are all important factors.

But what we’re missing most is sustained engagement with the residents of the city of Chicago. That’s how we can turn mere hacking into real innovation. The magic combination of government, developers, and community members is what we’re after.

First, let’s take a look at what’s working in the civic hacking world.

A rich baseline

Chicago has a long history of public data projects. I outlined a lot of this in a 2011 blog post, “Incomplete Take on the History of Open Data in Chicago”. Examples come from journalism (the Tribune’s 1986 series “American Millstone: An Examination of the Nation’s Permanent Underclass” used data to back up the narrative), government (the Chicago Police Department’s groundbreaking Citizen ICAM (Information Collection for Automated Mapping) database, and pioneering groups like the Illinois Data Exchange Affiliates.

Other elements include a recent history of influential data projects like Adrian Holovaty’s 2005 Googlemap mashup, Chicago Crime, which helped lead to the Googgle Maps API, Harper Reed’s 2008 “unofficial” Chicago Transit API, which helped unleash a slew of innovation around transit apps internationally, and the work of the Chicago Tribune News Apps team, which set a new bar for data journalism and created useful generic tools upon which other hackers can build.

An engaged developer community

A central component of the civic hacking scene is Open Gov Hacknights started by Derek Eder and Juan Pablo-Valez. They run the hack nights every Tuesday at 6:00pm in space provided by Smart Chicago at 1871 in the Merchandise Mart building. Beginners are welcome, and there is a continuity of work, as people share their progress from week to week.

Government that cares

There wouldn’t be much civic hacking without the support of government. Huge troves of state, county, and city data can be found at http://metrochicagodata.org/. Government officials and workers like are critical members ot the developer community. This past Tuesday, Kevin Hauswirth from the Mayor’s office stopped by to talk about digital.cityofchicago.org. OpenGovChicago has hosted presentations from Chicago CTO John Tolva, State of Illinois CIO Sean Vinck, and staff at the County Clerk. This month we’re working with the Ilinois Department of Employment Security.

Support from institutions

I’ve come to appreciate the key role of institutions, underpinning and financing this work. Thanks to them, we provide civic hacker community a guaranteed space to work at no cost to civic hackers. We provide server space for many of these civic apps. Our Civic Innovation in Chicago project is a good example. The project is funded by a Knight Community Information Challenge grant provided jointly by the Knight Foundation and The Chicago Community Trust. The MacArthur Foundation provides additional funds, as well as strategic guidance, for our work. This allows Smart Chicago to directly pay developers like Derek Eder, giving day-job pay on what used to be a nights and weekends pursuit.

What’s currently missing? The people.

All of this is great. Two important components for civic innovation, government and developers, are here in force in Chicago. But dozens of developers looking at each other in conference rooms over pizza is never going to lead to making lives better in Chicago without the active involvement of real residents expressing real needs and advocating for software that makes sense to them. The good thing is that Chicago has assets in this area as well.

We have a long history of citizen-led battles for just policies that are informed by data. Consider that the fight against redlining was centered in Chicago:

Following a National Housing Conference in 1973, a group of Alinsky-style Chicago community organizations led by The Northwest Community Organization (NCO) formed National People’s Action (NPA), to broaden the fight against disinvestment and mortgage redlining in neighborhoods all over the country. This organization led by Chicago housewife Gale Cincotta and Shel Trapp, a professional community organizer, targeted The Federal Home Loan Bank Board, the governing authority over Federally chartered Savings & Loan institutions (S&L) that held at that time the bulk of the country’s home mortgages. NPA embarked on an effort to build a national coalition of urban community organizations to pass a national disclosure regulation or law to require banks to reveal their lending patterns.

Everyone loves CTA Bus Trackers apps, but few people know that the GPS satellite technology making that possible is the result of lawsuit brought by a group associated with the Americans Disabled for Accessible Public Transit. Their case, Access Living et al. v. Chicago Transit Authority, required “installation of audio-visual equipment on buses to announce bus stop information to riders who have visual impairments or are Deaf or hard of hearing”. When you hear the loudspeaker system announce the next street the bus is stopping at, you have defacto data activists to thank.

We need you. Your city needs you. Write me at doneil@cct.org. Call me at (773) 960-6045. Get a mitt and get in this game.